How do we know what we do is right? Outwardly we may

stand firm with an expression of total conviction but only we know what goes on

internally. How do we know the right thing to do? What are the laws that govern

the actions of man accounting for what we call poetic justice? Are our actions

motivated essentially by selfless principles, or are they vain and egocentric?

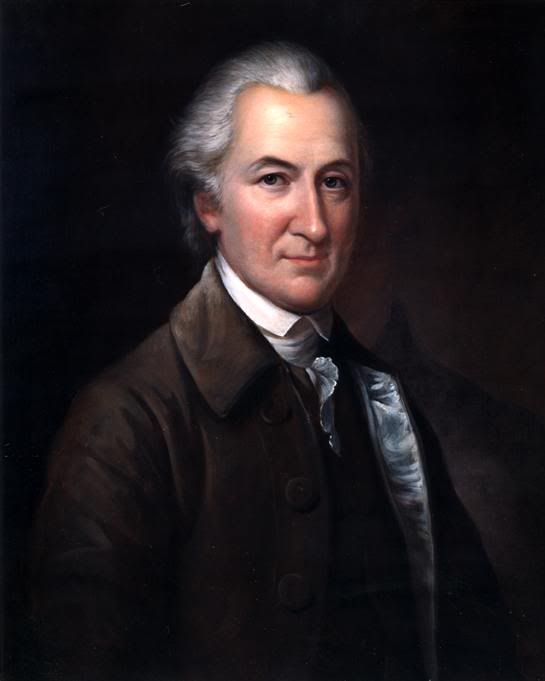

Or worse yet, cowardly? In the case of John Dickinson, one of the three

representatives from Pennsylvania who attended the Second Continental Congress

during which the Declaration of Independence was adopted, he clearly did the

wrong thing. The account that follows is a summary of the events surrounding the tensest moment during the foundation of the United

States. John Dickinson was 41 and either out of misguided loyalty, fear, or

some other negative motive – missed the opportunity of one thousand lifetimes.

I was puzzled why Dickinson, a tobacco plantation bred native of Talbot County,

Maryland sided with the British, at the cost of his posterity? Here are the

rudimentary facts from which we could theorize an answer or two.

Dickinson was born to an exceptionally wealthy family

with deeply anchored British roots. At the age of 18 he met George Read, also a

signer of the Declaration despite his initial splitter votes on behalf of Delaware. Read was from Newcastle, Delaware, and along with Thomas McKean, and

hard-core patriot, Caesar Rodney the three comprised Delaware’s delegates to

the Congress. Rodney’s exemplary skills, wit, and humility secured him a

crucial place in the history of the United States. In comparison to the outward

Dickinson, Rodney was the complete opposite. He was not quite 40 years old at

the time of signing and although a lawyer like Dickinson, the latter boasted

quite an inner-circle.

Young Dickinson studied law at Middle Temple, in the

city of London, or as it is formally known, The Honorable Society of the Middle

Temple. This name is supposed to refer to one of four ‘Inns of Court’

exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers.

The other three are the ‘Inner Temple, Gray’s Inn and Lincoln’s Inn’. Anybody

who has had a passing brush with stories of the controversial Jacques de Molay

may find further evidence of elite-Britain’s penchant for conceivably weird,

ritualistic tradition in that in the 13th century, these ‘Inns’ were originated by the Knights Templars as hostels and schools for young, student lawyers. Isn’t that… special? I find my curious imagination wondering what life

for so many young men was like while ‘studying’ in these ‘inns’? Perhaps I’ve

become cynical since the Jerry Sandusky outing. In summary, John Dickinson

received the most prestigious British education a young man could hope for in

his day, and ours.

Due to shifting circumstances after the war began,

Dickinson found himself residing both in Philadelphia and in Delaware. His

home, and where he had prospered his political career was Philadelphia. During

the war his Philadelphia home was seized and used as a hospital. King Charles

II originally gave the lands of Delaware and Pennsylvania to William Penn in

settlement for a financial debt the King owed Penn. It would be safe to assume

Dickinson’s ties with the interests of the British Empire were more than

passing friendship and more than likely involved banking investments. The

‘Crown’ was making a ton of money from the colonies. Why would they want to

change that? Dickinson appears to have been rather close to the British fire

and he consistently voted down attempts at independence, wishing instead to

argue on behalf on reconciliation.

Whether voluntarily or politically suggested, John

Dickinson was absent for the unanimous vote required to adopt the Declaration

of Independence and formally announce to King George the formation of the

United States. Benjamin Franklin, on behalf of Pennsylvania voted for adoption,

and in one of the most dramatic events leading up to the signing of the

historical document, Ceasar Rodney made the now famous ride from his home in

Dover, Delaware to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in time to cast the deciding vote

for a Delaware majority in favor of adoption. At the risk of rapidly failing

health due to skin cancer Rodney dedicated his life to the struggle that

ultimately resulted in separation from the tyrannical rule of King George. With

the rank of ‘Brigadiere General’ of the Delaware militia, Rodney fought

alongside George Washington in the Battle of Yorktown, and Dickinson served

under him. In downtown Wilmington, Delaware there is a statue of Caesar Rodney

on his horse, immortalizing the famous ride. He is also commemorated in

Delaware’s State quarter. I will propose that even with a fleeting glance at

this story you too will agree Rodney did the right thing. He had no Ego

whatsoever and as proof he died unduly young at 48 due to unattended health. He

is buried in his farm in Dover and in over 200 years, he has not been

forgotten.

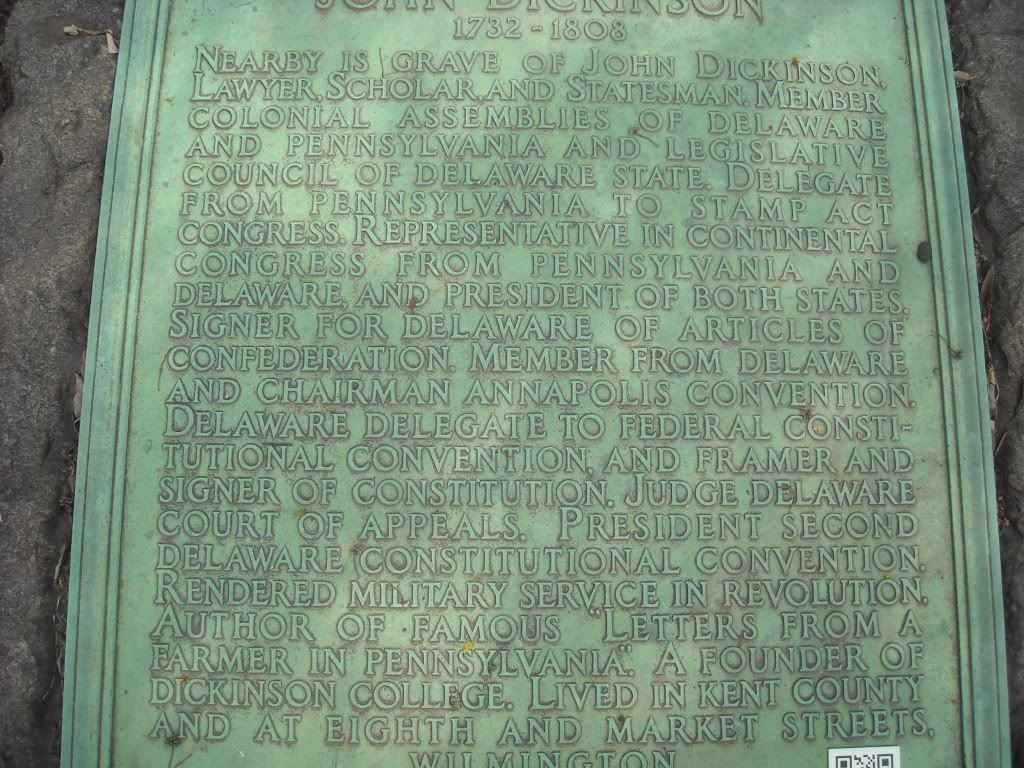

During the Revolution and in the years after Dickinson

was involved in the shaping of the country’s rule of government but nobody

respected him. He is not a particularly known figure associated with the

foundation of our government. There are the Founding Fathers and that’s it.

Nobody knows of John Dickinson but maybe now, with his new App, and my article,

his littered grave in the heart of the ‘hood may see a little more action.

Watch First for Friday, June 29, 2012 on PBS. See more from First.